My brother Mobutu is dead

and I wonder what he was wearing to warrant him waylaid

with a rifle. What part of his dusty clothes

had enough garden soil to convince his killers

to plant a bullet.

I told him, I told them all, my little cousins,

Your parents have too many mouths to feed

and bleach is a luxury this house cannot afford,

so when you’re on the playground

keep clean!

My people are walking bibliographies.

Our elders say that a man’s attire utters many things

long before he tells you his name.

And so when the community school was tumble-washed

and the maggots began eating the bookworms the day after the cleansing,

we taught ourselves the dialect of clothes –

how to read a ‘text-tile’ long after the body has fled:

Nzola —no crease on belly button— worn on an empty stomach

see starched-yellow smear here —caught cold— tried to wipe nose

Safi —played Nzango with friends— see stampede-brown here

went tree climbing— see roughened patches here— and ran— or tried to

Ilunga —smells of lavender and river wetness— smells of the Rusizi

child —forgive us —all the rivers you swam across to safety

could not wash the war from your skin

Tatu —who wears prison-orange for clothes?— smell armpit here

see rumple see rumple see rumple here

How many hands tried to unwear you but your own?

See torn seams here— see collar is bent like a pleading palm

Hands hold —Hands grab —Hands do not listen— semen here

I am trying to find Mbuzi’s shirt in the pile. It is a white polo

splashed with blood art.

He found it funny that a machete

———–slashed a clean line through his afro,

Mama ————I almost look like Lumumba now.

Because hell is full of infants, something in the night

recruits lactating mothers to feed them.

Because cleanliness is next to godliness, how much longer

until we are ethnic-cleansed enough to be God’s people?

Ahoy! Is anyone coming to save us, Ahoy!

Don’t these gun fires send up enough smoke signals?

Ahoy! My people are dying to be heard,

my people are dying to be seen.

Fuck the media who never wrote about us until we were dying!

Fuck you if you don’t see that all your iPhones

are pheresis bags with pints of our blood.

Fuck the foreign francs-euros-dollars funding the family feud.

When brothers go to war, it is the nephews who get slaughtered.

I know, I know, people in pictures do not move, I know, I know.

When the search party found Mobutu on the evening bulletin

and I tried to motion him from the paper, I said

Get up brother, get up and let us go now. You have school tomorrow.

Look you don’t have to do the chores.

Look, I swear, I am doing all this laundry for you, soon it will all be clean now.

Get up, you silly beautiful beautiful boy!

I am still washing for the mother

who does not want their boys to be buried without clothes.

I am washing for this town

which will need clean shirts for white-collar jobs

when the occupation ends.

I am washing because it is what you do when there is nothing else to hold.

I am washing for the poets who pen the persecuted,

the dancers who bend bodies to move conversations,

the chanters invoking fire and smoke clouds at the altars of justice,

the artists who strip themselves to wear Goma on their skin.

I am washing because this country needs fresh laundry to make a peace flag.

Something clean to be rinsed, wrung and spread out in the front yard.

Because a swaying clothesline only means that the wind has not died

and the sun will rise again.

*

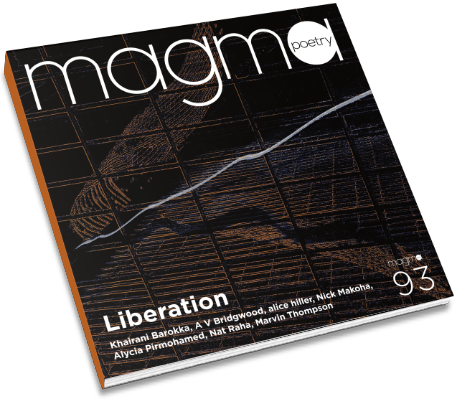

From Magma 93

Buy this issue for £8.50 in UK (including P&P) »Buy Now

Supported by Arts Council England

Supported by Arts Council England