I have Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o to thank for inspiring my poem Hollywood Africans, an ekphrastic, prose love poem in The New Carthagians (2025), a book that centres on a resurrected Jean-Michel Basquiat, a Black Icarus and me, the Poet. Ultimately, Hollywood Africans – both the 1983 painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat and my poem of the same name – serve as critiques of American culture (a proxy for Western culture) and its narrow frames for Black identity. The works are assertions of Black self-determination and interiority, rejecting historical erasure and offering instead a vision of cultural and psychological freedom.

So what does that have to do with Ngũgĩ? Ngũgĩ is a catalyst for the African voice to speak out against erasure.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, born in colonial Kenya in 1938, was shaped by the Mau Mau rebellion and came of age during a time of intense anti-colonial resistance. For him, true freedom required a decisive break from colonial structures, particularly the English language, whose dominance he saw as estranging and alienating to Indigenous culture. For Ngũgĩ, liberation was not just a thought experiment but a tool for resistance – because colonialism isn’t just a political system, it’s an aesthetic project, a way of structuring the world and its knowledge. It imposes narratives, languages and structures, and stifles our voices. Ngũgĩ, rooted in African realism and socialist politics, refused to let this colonial violence write the final word.

Across his work – including Decolonising the Mind (1986), Petals of Blood (1977) and A Grain of Wheat (1967) – Ngũgĩ ’s steadfast critique of neocolonialism and cultural imperialism speaks to ongoing struggles against globalisation and the dominance of corporate-controlled knowledge. His call to decolonise the mind and return to Indigenous languages and grassroots art is a plea for their sovereignty in a world that continues to erase and homogenise important groups of society. For writers like Ngũgĩ, who recently passed at the age of 87, liberation – whether political, cultural, psychological or linguistic – is central to African and diasporic literature. Ngũgĩ views the writer as a revolutionary intellectual, using literature as a tool for political change rather than an escape from it. And in today’s world, shaped by rising authoritarianism, environmental exploitation, racial violence and the increasing grip of nationalism, the relevance of our art as a form of resistance becomes even clearer.

In Writers in Politics (1981) and Decolonising the Mind, Ngũgĩ argues that writing is an ethical choice between resistance and silence, truth and complicity. Eventually, this conviction led him to abandon English for Gikuyu, a radical act intended to dismantle the colonial language hierarchy and affirm Kenyan cultural identity. His vision extended beyond the written word to community performance. Through the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre, he helped to stage plays like Ngaahika Ndeenda (1970) in open-air venues, making theatre a form of political education that addressed land dispossession, gender inequality and class struggle. His activism ultimately led to his imprisonment, which deepened his belief that the writer must confront political power. In Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary (1981), he reflects on the links between artistic freedom and repression, asserting that true liberation depends on cultural autonomy. For Ngũgĩ, the writer is not just a storyteller but a custodian of memory, a critic of injustice and an architect of a more just future.

So Ngũgĩ is an agent of liberation – the word coming from the Latin liber, from which we get the liberare (“to set free”) and the noun liberatio (the act or process of freeing). The word “liberation” encapsulates both the desire to be free but also the ongoing processes through which freedom is pursued and continually redefined. Initially used in religious contexts to denote spiritual release, liberation is a continual movement from oppression to freedom. The word is now a part of political discourse, where it has come to symbolise the overthrow of monarchies, the pursuit of self- governance and the recognition of individual rights. Ngũgĩ ’s novel Weep Not, Child (1964) explores colonial Kenya during the Mau Mau Uprising, telling the story of Njoroge, a boy who hopes to escape poverty through education. As political violence grows and his family becomes entangled in the struggle against British rule, Njoroge’s dreams begin to fall apart. The novel studies the harsh realities of colonialism and its impact on individuals, families and society.

Liberation is not a singular, finite event but a constellation of acts: writing a poem, performing a play, remembering a name, refusing a language, raising a voice. These acts, though they may seem small, are cumulative, and in that accumulation, they hold power. For Ngũgĩ, liberation is a creative act: an ongoing practice of survival and self-definition that rejects the notion of the artist as a neutral agent. Accordingly, Ngũgĩ ’s characters often face deep moral and spiritual reckonings. In Devil on the Cross (1980), Wariinga, a young Kenyan woman, returns to her hometown after facing exploitation and hardship in Nairobi. Along the way, she attends a bizarre gathering called the “Devil’s Feast”, where powerful elites boast about their corruption and exploitation of the poor. As Wariinga awakens to the roots of her oppression, she transforms into a symbol of resistance against neocolonial greed and injustice. Wariinga’s resistance is dual: outward, in pursuit of political justice, and inward, toward reclaiming self- respect and autonomy. True liberation isn’t only legal, it is personal, emotional and spiritual. It is the ability to imagine, love, speak and dream without fear.

It was with this confidence that I took up the challenge as a Black body to reclaim Carthage. To me, Carthage itself – a North African city from which Hannibal Barca hailed – represents a powerful African civilisation long overshadowed by colonial narratives. Though founded by Phoenician settlers, Carthage evolved into a hybridised African polity that rivalled Rome. Hannibal’s military campaigns are a pre-modern embodiment of defiance against empire; in particular, his legendary crossing of the Alps with African war elephants were not just strategic manoeuvres but acts of resistance. This resistance, though predating modern racial categories, mirrors the struggles of African nations and the Black diaspora against European colonial powers. In a postcolonial context, Carthage reminds us that Black history stretches deep into antiquity, long before European colonisation. In my work Carthage, once a defeated city in the European imagination, becomes a site of African pride and identity, a place where myth and history collide to tell the story of diasporic resilience.

In my latest collection, The New Carthaginians, Basquiat, Black Icarus and myself, the Poet, are Carthage’s spiritual descendants. The struggle for representation by reclaiming figures like Hannibal and Carthage is not a simple act of nostalgia; it is an insurgent act. It challenges the erasure of Black identity from world history and repositions it within the broader narrative of global resistance.

Consider J M W Turner’s depictions of Carthage, Dido Building Carthage (1815) and The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire (1817), which capture the rise and fall of empires. One landscape bathed in golden light, the other in fading dusk – echoing the fragility of both physical and ideological power. The journey of liberation is both radiant and impermanent. In Turner’s paintings, there is a recognition of empire’s transience. Yet despite the North African setting, the gaze is white. In response, this erasure of the Black body is what Basquiat explores, particularly through his powerful depictions of African Americans in the context of systemic racism and cultural erasure. His canvases, often layered with text, fragmented bodies and abstract figures demanding to be seen and acknowledged, assert Blackness as an integral part of global history.

In Hollywood Africans, he uses fragmented text to expose the violence of colonial languages and cultural dislocation. Phrases like “SUGAR CANE” and “TOBACCO” serve as painful reminders of the history of slavery and colonialism, while terms like “GANGSTERISM” critique the commodification of Black identity in Hollywood. The disjointed, layered words in his art force the viewer to confront the contradictions and absences inherent in the representation of Black people in the West. Across his work Basquiat rejects simple, linear narratives in favour of exposing the fractured, complex nature of Black identity in a world that continually attempts to simplify or distort it. He critiques the myth of Hollywood for Black actors: its illusion that mainstream success, visibility, or inclusion equals freedom, power or true representation. In reality, the industry often offers only a carefully managed spotlight, bounded by typecasting, marginalisation and systemic barriers that remain deeply entrenched. The painting features a version of himself alongside friends Toxic and Rammellzee, set against a backdrop of interwoven, layered and elliptical words that expose the commodification and stereotyping of Blackness in American culture. It’s both a refusal to be reduced to caricature, and a reclamation of Black identity from the clutches of erasure.

In my ekphrastic poem, also titled Hollywood Africans, I engage with Basquiat’s themes by replacing Toxic and Rammellzee with myself and Black Icarus. Just as Basquiat challenges the absurdities and alienations of the “Hollywood African” label, laden with histories of exploitation and racial commodification, I challenge the canonical love poem, so often attributed to figures like William Shakespeare, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, E E Cummings, and Carol Ann Duffy. My aim was to insert a contemporary African voice into that tradition, and to complicate what love – particularly Black love – can look and sound like, showing that it is not a monolith but a rich, multifaceted experience.

Just as Basquiat used his codified imagery to subvert dominant narratives, I blend the surrealism of James Tate with Afro-diasporic and Afrofuturist elements in my prose poem. The result is a hybrid, cinematic text that refuses to conform to Western representations of Blackness. It resists tropes of suffering, fetishism or symbolic use and instead insists on Black love’s beauty, vulnerability and multiplicity. Through this filmic aesthetic, the poem becomes a tool of resistance, forcing the reader or viewer to confront how deeply racial bias shapes our understanding of intimacy and desire.

The gathering and reclaiming of lost stories is a radical form of resistance, challenging the linearity of colonial historiography and rejecting the commodification of trauma. Inspired by Ngũgĩ ’s reclamation of Gikuyu as a political act taken at personal risk, my own poetic form of reclamation is not a personal choice but a refusal to let the language of empire dictate African expression. In doing so, I aim to redefine the relationship between Black identity and creative autonomy.

As long as we continue to write and resist, we contribute to the ongoing struggle for liberation, ensuring that the horizon of freedom remains within reach. Liberation demands constant reimagining and cannot be reduced to a political victory or a singular act of defiance. Such freedom is not a final destination but something we must continuously create through our stories, our reclaimed tongues, and the broken forms we make whole again. It fosters a poetics of vigilance, a refusal to forget, a continued resistance and an ongoing search for a way of being that we constantly create, rebuild and reimagine, through both our actions and our narratives.

*

Dr Nick Makoha is a Ugandan poet, playwright, RSL Fellow and Founder of Obsidian Foundation, based in London. His latest collection is The New Carthaginians (Penguin, 2025).

*

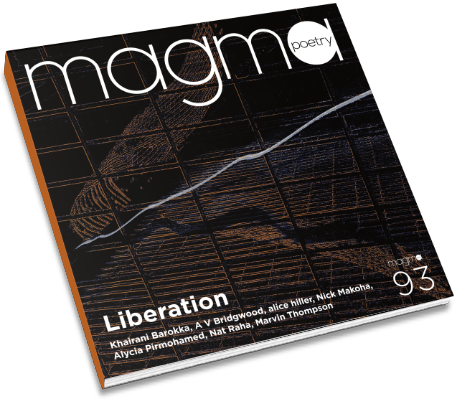

From Magma 93

Buy this issue for £8.50 in UK (including P&P) »Buy Now

Supported by Arts Council England

Supported by Arts Council England