As I approach my twentieth year as a performer and activist, I have cause to reflect on spoken word in Trinidad and Tobago. I am thinking about the labour taken on by many people, in and out of the “movement”, who have created space for writers and performers. The great orators of our region do not come to mind first; rather the writing and publishing forces that sacrificed to ensure poetry had its place in an independent nation. Between 1973 and 1993, Anson and Sylvia Gonzalez, a publishing duo unlike any other, likely bound together more paperback collections than anyone else in the region. They founded New Voices, a “little magazine” that was instrumental in bringing Caribbean writers, namely its poets, to the public. Their lives, mirroring those of the majority, involved full-time jobs, hobbies and nurturing a vibrant community of readers and writers at the Public Library of Trinidad.

Defining national and regional aesthetics, poetics, and ‘traditions’ within 20th-century Caribbean literature was a thankless endeavour. It was an act of constant pleading in the early stages of post-Independence nation-building, a persistent effort to instil in Caribbean people confidence in the value of their place-based stories, voices and imaginations. Over time, Anson and Sylvia’s New Voices transformed from a modest magazine to an upstanding literary journal, eventually becoming an archive of Trinidad and Tobago’s most enduring poetic voices. Within its pages lay an archive of creative ventures and postcolonial critique, including people across the Caribbean who found fertile ground for their imaginations in Trinidad and Tobago’s multicultural, multiethnic cosmopolis. The journal itself became a shelf, a space for what was then called “West Indian Literature” – a repository for an archipelago and an America on their quest for self-determination.

Anson and Sylvia would never have called themselves activists, yet their relentless mapping of a people’s imagination – in a society where our bodies were captured, capacities underdeveloped, politics deliberately oppressed and voices excluded from the classrooms of a socially engineered colonial education and literacy – was an act of resistance. To affirm the value of one’s own memory in such conditions was a radical act of freedom against the violence of erasure. New Voices extended the readership of a generation of homegrown writers, including Victor D Questel, Jennifer Rahim, Lisa Allen-Agostini and Dionne Brand, and literary critics such as Kenneth Ramchand and Gordon Rohlehr. The New Voices Newsletter, run from 1981–1993, was a community-building publication that shared publishing and award opportunities, and the latest news in Caribbean literature. In the end, New Voices platformed more than 300 Caribbean writers in its pages.

Steelband Saga, A Story of the Steelband: The First 25 Years – I remember the slim publication by Sylvia Gonzales next to my mother’s computer. During her career, Sylvia authored a number of publications on childhood education and short stories for children. Anson was the accomplished poet of the pair. Artefacts of Presence: Collected Poems, 1964–2000 (2010), published by Peepal Tree Press, assembles decades of Anson’s journal and self-published poetry books. He often wrote in free verse, but until the end of the 20th century he distinguished himself with the haiku form and prose poems. Yet the reality of his life, as an architect of Caribbean literature, educator, professional photographer, martial arts practitioner and marathon runner with family obligations, meant spending significant time publishing the work of others; his own stanzas were sometimes relegated to the quiet corners of bookstores. This was especially true during the long decade of the 70s, when “Revo” and “Black Power” brought forth newer voices inspired by dub poetry, spoken word of the Last Poets, and the rise of rapso lyricism on the island, even casting a wary eye on the reserved temperament of a “Red Man”. With little tribute to his and Sylvia’s immense sacrifice, save for the quiet acknowledgment of a few friends scattered across the Caribbean and its diaspora, it is no surprise that Anson’s own poetry has, like a faint echo, receded into the errata of collective memory.

My mother and father held Anson in high regard. They spoke of Sylvia with a tenderness that still resonates. Anson Gonzalez, to me, was always “Uncle Anson”. He publicly applauded my father, crediting him for a friendship that spanned decades and for encouraging his efforts as an editor and a writer. My father, who believed every poet was a seeker of dignity on the death grounds of colonies, saw wordsmiths and their curators, like Anson and Sylvia, as quiet liberators of the conscience. He believed in Anson, and in the freedom of his song.

I didn’t truly meet Uncle Anson until I began writing seriously in secondary school around 2005. Back then, my notebooks overflowed with poems born from deep listening sessions of Bob Marley’s Babylon by Bus and student-led petitions against Grooming Policy and Hair Codes in school. My mother, bless her, enrolled me in a writing workshop facilitated by Uncle Anson. It was a small gathering, one Saturday morning. Most attendees were well into their fifties and sixties. I remember one woman professing her dislike for cricket, yet beautifully describing aloud the swan-like movements of Dwayne Bravo in a One Day International match, her spectatorship made possible by granular slow-motion replay on TV, a technology unthinkable in Anson’s youth. The poem she read, however, was poorly written. Uncle Anson spoke softly and his critiques were gentle. Without any posture of an editor who had helped shape the national and regional literary space, he had a wide embrace for everyone’s work. Sometimes, a fleck of spit clung to the corner of his mouth. He’d lean in to speak, and his breath was the breath of an old man. He was ill.

In some ways, he struggled to bridge the generational gap between him and me and another poet, Arielle John, who was a year ahead of me in secondary school. We were the “youth” attendees. Our parents were eager to send us to apprentice under Anson. I remember his bewilderment when he read Arielle’s poem. “Free verse”, he muttered, “written in dialect”. He spoke of his friend’s son – the son of an English Literature teacher. He had migrated to the US as an adolescent, excelled in poetry slams and grown dreadlocks. Yet, what Arielle wrote and read those Saturdays was the only poetics that truly resonated with me in the workshop. We both, inevitably, dropped out. Our parents understood. And I, too, always understood Uncle Anson. He was an educator, a man who taught the rules of grammar and standardised English to ensure Caribbean children had every chance to succeed economically, to connect with a wider world, full of rules.

Arielle, though, was a spoken word poet. She texted me later about an open mic in Port-of-Spain, part of “the movement”. Through her invitation, my words, inspired by the printed verse of Oxford anthologies and the little presses of Tunapuna and Port-of-Spain in Trinidad, found a new purpose. I joined a cause to awaken the poetic and political consciousness of youth through nation language, to speak in communities where others feared to tread, to challenge the gatekeepers of literature and its traditions. There was a world of poetry far wider than books, something inherent in the very language, landscape and lives of everyday people. And I urgently joined, eager to dismantle any small shelf we had been relegated to in a Caribbean literary tradition and society in formation.

When we spoke of “spoken word”, we meant rented amplifiers on the temporary stages we had built. We meant flyers, printed on home computers, tacked to secondary school and university walls in dizzying orientations. The few open mics, once confined to the capital city, flowed east and south and “up de road” to Tobago, assembling new concerns, voices distinct from the university-educated, urban, petty-bourgeois class. And make no mistake, though many among us carried “African names” and names of Third World liberators in the wake of the 1970 Black Power Revolution and the 1990 Coup, and though our hair was natty and natural, though our bodies were draped in textiles from African and Indian fashion houses, we were, largely, products of the island’s prestigious denominational secondary schools. The very colonial focus on English Literature, ironically, became the breeding ground for a new generation who questioned the curriculum, who borrowed from popular cultural forms like the Midnight Robber and Pierrot Grenade to rage against colonial continuities and their presence a ghost in our texts.

Before the allure of poetry slam prizes, before the embrace of radio and television cameras, spoken word was a youth- led social movement building stages. It was a movement for literacy, where we went into schools and facilitated workshops on literary devices and the role of poetry in everyday life. It also involved the cultivation of literary publics, leaving behind no square foot on a basketball court, trade union hall or after-hour bar to share spoken word and bring to the stage local musicians who were not on mainstream media. The movement was indeed part of a nationalist mood, seeking to turn the focus of leaders and decision-makers inward, to define the country’s social, economic and political path from within, with human resource development as the marker for progress.

Among us, there were currents of division, yes. Our engagements ranged from youthful excesses – debates over skipping university exams for an environmental protest – to the more divisive confrontations, when spoken word poets, driven by their visions, lent their voices to political parties in our two-party system, where competing ethno-cultural narratives vied for state power and social advantage. There were questions about inclusivity of Tobagonians, Indians and young women in the movement. In many ways, this is the bacchanal that Uncle Anson stayed away from; it was the bacchanal I ran toward.

When spoken word, in its highest form, lit fires on stages, we flung shoes at performers as an offering of applause. We hurled shoes at spoken word poets, after Muntadhar al-Zaidi, in a fleeting, defiant spectacle, removed his own and sent them flying at George W Bush, a punctuation mark at the end of a presidential term. In that season, the spoken word echoing through international media for nearly a decade was “Weapons of Mass Destruction”. Four words, a drumbeat repeated by a president, by Colin Powell – a man the Caribbean claimed as its own – and by news houses across the Atlantic. These word-sounds, with their built-in rhyme, promised only death, bombings and ash. Ash that poets reimagined as snow because they refused to speak in absolutes of the wicked and the ugly.

The very ground where we first cast our shoes in praise of a poet was once known as the JFK Shuttle Station at the University of the West Indies. We later renamed it the Bay of Pigs Station, and there, we performed poetry, free from the threat of missile attacks in an air whose sovereignty imperial countries had not yet fully accepted.

Uncle Anson died in September 2015. He was in Wales; a past poet laureate of Port-of-Spain seeking a dignified end for his final breath, nearer to family and quality systems of healthcare. It was his hand that scattered the seeds of National Poetry Day in Trinidad and Tobago, a day inconsistently observed, kept alive by the quiet activism of librarians and the persistent tending of secondary school teachers. My father, a man whose love for words ran deep, had already departed in March that year. Before my father’s death, Uncle Anson had not relinquished his role as educator and editor. In 2011, he wrote to me on Facebook: “Take this with love, Amílcar. Find a book, chapter, or website on words commonly misused/misspelt. Give yourself Respect, a short workshop like 3 weeks on this aspect. Your written and perhaps even spoken words would improve remarkably.” His voice, even now, pulls me towards structure, towards his discipline and grace.

I find myself an inheritor of struggles, standing on both sides of poetry’s table. I must break down the walls of rooms that domesticate literature, turning away from the hagiography of authors with MFAs and degrees bestowed by Global North academies. I understand the history that explains exactly why writers who leave and succeed “away” and in the “cold” are alchemists in the Caribbean and have their books return home on a higher shelf. I also inherit Uncle Anson’s quiet fight to print the voices of modest writers here – writers who yearn to know that not only are their words worthy, but they themselves are worthy people. Uncle Anson and Sylvia made us worthy, their battle fought without a microphone, their errata a testament to their ambition. I write and speak the way I do because of them.

*

Amílcar Peter Sanatan is an interdisciplinary Caribbean artist, educator and activist. He is from Trinidad and Tobago, currently working between East Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Helsinki, Finland. He is the author of two poetry chapbooks: About Kingston and The Black Flâneur: Diary of Dizain Poems, Anthropology of Hurt.

*

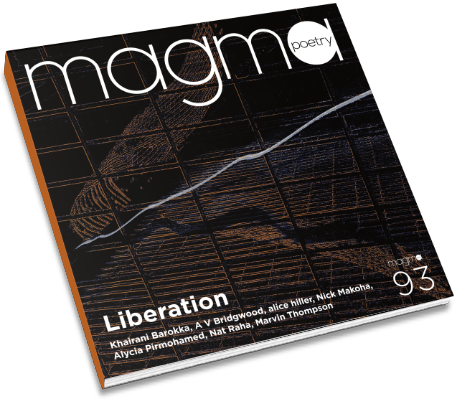

From Magma 93

Buy this issue for £8.50 in UK (including P&P) »Buy Now

Supported by Arts Council England

Supported by Arts Council England